Nearly painless, occasionally fatal: What’s it like to get bitten by a rattler?

‘The tip of my nose and my lips got numb, and I said ‘Ah, I’ve been envenomated.’

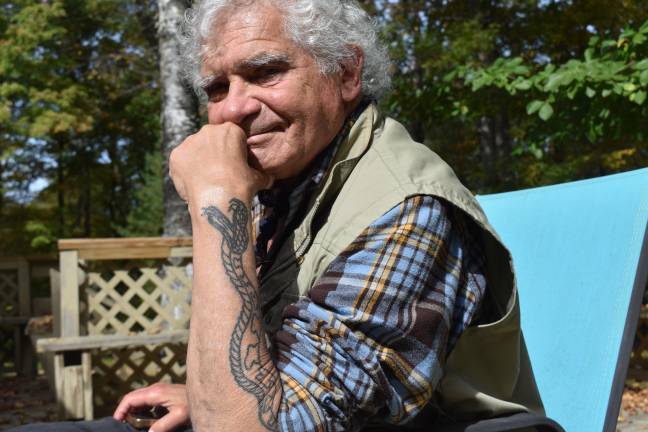

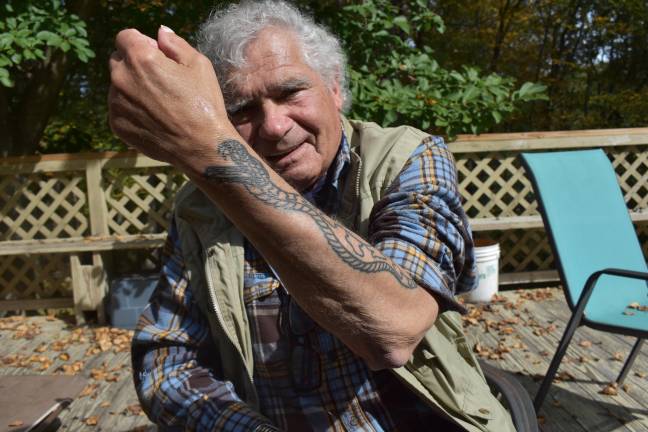

Marty Kupersmith, a musician then in his 70s with a lifelong love of reptiles, was relocating a timber rattlesnake that had been in someone’s doorway in Greenwood Lake, N.Y., when he got bitten in 2018.

After responding to a police call for a nuisance rattler, he’d kept this gravid female overnight, fed her a roadkill chipmunk, and along with a friend, was hiking her up to an appropriate release spot in an old pillowcase when he started to have a mild asthma attack. He decided to release the snake then and there.

Kupersmith, a state-licensed snake handler, was holding her by her tail in order to get his black marker, a practice (since abandoned) that let him know when he encountered a rattlesnake multiple times – “when in less than the blink of an eye she crawled up the length of her body and bit me on the left forefinger.” She had defied the rule he’d always known to be true, that snakes can only lift themselves half their body length. It felt like a yellow jacket sting but less painful, he said.

“I’ve been hit,” he told his friend.

New Jersey State Senator Parker Space, owner of Space Farms Zoo in Beemerville, N.J., was feeding his captive massasauga rattlesnakes dead mice when he got bitten on the finger in 2024 by a snake he thinks mistook his hand for a mouse.

Both men initially hoped the bites were “dry” – sometimes rattlesnakes don’t release any venom when striking defensively – but quickly realized they were not.

“I didn’t feel anything, so I kept feeding other stuff. Within minutes the tip of my finger started swelling up,” said Space, 56. Space had been bitten by a variety of snakes over the years, but never a venomous one.

“I saw where she bit me there was a clear substance, and the tip of my nose and my lips got numb, and I said ‘Ah, I’ve been envenomated,’” said Kupersmith. “I called 9-1-1, they said sit down, don’t keep moving ‘cause it’ll circulate the venom. So I sat down on a rock and I waited and they came.”

Time is of the essence after a venomous snakebite. Kupersmith was taken by ambulance to St. Anthony Community Hospital in Warwick; Space drove himself to Newton Medical Center, where they had to cut his watch off his swollen wrist. Both received antivenom.

Space’s swelling got so severe later on that doctors considered cutting open his arm, a course of action his snake buddies advised him to refuse. The morphine they gave him did little to ease the pain from the pressure of the swelling, said Space. “I was trying to get my wife to get me a bottle of Jim Beam. She wouldn’t do that.”

Eventually, both men were transferred to Jacobi Medical Center’s Snakebite Center in the Bronx for observation, the tri-state’s premier snakebite treatment facility, which works in conjunction with snake experts at the Bronx Zoo. The Snakebite Treatment Center treats about 10 patients a year, primarily copperhead bite victims, said Dr. Joshua Silverberg, the Center’s director. “Many patients are trying to handle the snake in some way,” he said.

Kupersmith had a lot of visitors while in the hospital “because everyone wanted to see the schmuck that got bit by a rattlesnake,” he said.

Both made full recoveries, though Space had to go back to the hospital when he got a bacterial infection a couple days later.

Or almost full recoveries.

Now, when it’s below 40 degrees out, or when Space is working in the zoo’s walk-in freezer, “if my hand gets cold, the tip of my finger gets purple and goes numb. It feels fine. Must be a little bit of nerve damage.”

In Kupersmith’s case, his friends worried: a guitarist with the rock band Jay and the Americans, Kupersmith needed full range and feeling in his hands. But once the swelling of his arm subsided, the bite left behind no long-term issues, just a commemorative rattlesnake tattoo on his left arm.

“My guard’s back up,” said Space, who bought feeding tongs online from his hospital bed, thinking of his cobras, which could end his life if he were not more careful. “When you’re used to doing this every single day, day in and day out, ever since I was a kid, I let my guard down.”

Kupersmith has quit marking rattlesnakes with marker, and for the moment he’s not going out on police calls because he’s recovering from a two-week coma he fell into after a bad asthma attack. “Oh God, I missed the whole rattlesnake season,” he groaned in late September. “They’re going back in soon.”

Neither Kupersmith nor Space has the slightest intention of steering clear of rattlesnakes. “If I get a call I’ll go, you know,” said Kupersmith. “I don’t know why I like reptiles. I don’t know if it’s my brain, if I have like a reptilian brain? Maybe I like the oppressed.”

The snakebite survivors’ club

And so Kupersmith and Space entered a sort of brotherhood. “Yeah, welcome to the club, it’s about time,” Space’s snake buddies told him, calling to bust his chops after they heard the news. His grandfather had been bitten several times by rattlers, he said.

“Almost everyone I know who does this has been bit,” said Kupersmith. That includes his friend Marty Martin, a renowned snake researcher in West Virginia, who became the most recent snakebite fatality when he died in 2022 at age 80 after being bitten by a captive timber rattlesnake. It was the fourth time he’d been bitten.

Being bitten more than once doesn’t give you an immunity; it can, on the contrary, make you more sensitive, said Randy Stechert of Narrowsburg N.Y., the foremost rattlesnake expert in the region.

“Rattlesnake Randy,” as he’s affectionately known, was bitten four times by venomous snakes between 1964 and 1992: twice by timber rattlers, once by a copperhead and once by a terciopelo in Central America.

Stechert scoffs at the notion of a brotherhood. “We the professionals, we don’t like to admit that we’ve been bitten. It’s kind of embarrassing, to tell you the truth.”

Rarer than getting struck by lightning

Between 7,000 and 8,000 people are bitten by venomous snakes in the U.S. each year. Thanks to modern medicine, only about five of them die, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Venemous snakebites are particularly unusual in the Northeast. “We are fortunate to live in a region where our venomous snakes are not as bad as some of the snakes around the world, and the antivenins we have access to are very effective and much safer than some in other countries,” said William Eggleston, assistant clinical director of the Upstate New York Poison Center.

In Upstate New York in the last decade, 264 snakebites (venomous and non-) were reported to the Poison Center, 51 of them in Orange County. The “vast majority” of victims were men, typically between 25 and 30. None resulted in a serious outcome, said Eggleston.

Snakes are active in our region until late October; most calls to poison control for snake bites occur between May and September. Timber rattlesnakes and copperheads are the two venomous snakes to be concerned about in this area. (Massasauga rattlesnakes are endangered and found only in small pockets upstate.) Both rattlesnakes and copperheads are pit vipers, distinguished by the heat-sensing pit organ located between the eyes and nostrils.

“In our hospital, we have treated only one venomous snake bite in the past couple of years,” said Dr. Michael Connolly, of Atlantic Health Newton Medical Center’s emergency medicine department. “The vast majority of snakebite encounters locally involve non-venomous species.”

Newton Medical Center stocks 30 vials of ANAVIP, a broad-spectrum antivenom effective against rattlesnake and other pit viper bites found in the U.S.

The last recorded fatal snakebite in the tristate region was in 2015, when Russel Davis, 39, was bitten by a rattlesnake by a campfire in Elks County, Pa., and died of cardiac arrest in the helicopter en route from one hospital to another. The cause of death was ruled anaphylactic shock.

Just as some people are allergic to bees or shellfish, some are allergic to snake venom and suffer much more serious reactions to a bite, explained Stechert.

Men are most likely to be bitten by rattlesnakes – and about a fifth of the time alcohol is involved, said Dr. Daniel Keyler, a retired toxicologist who specialized in venomous snakes. Keyler has been called into emergency rooms on New Year’s Eve not once but twice for drunk rattlesnake bite victims.

“Somebody has a, quote, pet rattlesnake in an aquarium, and their friends go, I can pick it up, you know. Next thing, they’re in the emergency room. So then you’ve got a drunk snakebite patient, which is always really entertaining,” Keyler said drily. “Snakes are smarter than people sometimes.”

Children account for about a fifth of rattlesnake bites and often suffer more severe reactions because of their smaller body mass, said Keyler. He recommends teaching kids from a young age to tell their parents whenever they see a snake. If it turns out to be venomous, the parents can decide whether to have it removed.

A disproportional fear

Though fear of snakes is among mankind’s most common phobias, you’re four times as likely to die of a lightning strike than a snakebite in this country, and 14 times likelier to die of a wasp or bee sting.

Contrary to media portrayals, snakes do not attack – but they will defend themselves.

“If you do see a venomous snake, it’s really easy just to stand back and slowly walk around,” said Keyler. “Don’t approach it, just back up and make a circle around it or retreat from where you came. But you don’t need to run or anything. Just be very conscientious of your environment, and when you see them, just give them space.”

Fear is a natural response to venomous snakes, and maybe that’s a good thing, said Stechert. “People have a lot more fear of them than they need to,” he said. “The fact of the matter is these animals are basically innocuous. Those people that get bitten generally are the ones that are harassing them.”

Even Stechert, who’s been working with snakes all his life, is not immune to that fear. “I know these animals, and I’m experienced, and it scared the sh** out of me,” he said, describing his last rattlesnake bite. “But nothing much happened as well. That is not atypical.”

Stechert’s last rattlesnake bite was “like a mosquito bite.” It bled significantly, thanks to the anticoagulant in rattler venom, “and I got a little local weal (slight swelling) surrounding the bite site, and that was it,” he said.

Stechert’s copperhead bite, by contrast, turned out to be the most serious of his four bites – which was surprising since copperheads are the least deadly of the three snakes with which he tangled. He was collecting the snake for a zoo when he was bitten on the arm, which swelled up “like a balloon” from fingertip to shoulder.

Can you kill a rattlesnake?

It is generally illegal to kill a rattlesnake or copperhead in New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania, though people do it anyway.

“Read in the paper yesterday the NYS DEC fined a guy for killing a rattlesnake! It seems they are rare in NY and they are protected to try and bring the population back up. I think the guy deserves a medal. If I see one on my place (not likely) it’s a gonner. I’ll know now however not to show it off,” wrote a commenter on a farming message board.

“You’re taking a key part of the energy chain out if you take the rattlesnakes away,” said Keyler. By killing a venomous snake, you may in fact be trading one perceived danger (the highly unlikely threat of a snakebite) for a much more probable one (the long-term risk of contracting a tick-borne illness). Large snakes provide all-natural rodent control. They get down in burrows and make a meal out of a whole litter of mice and the ticks they carry, said Keyler, helping to “keep a deer tick population from going crazy.”

If you want a rattlesnake off your property, you can call a pest control company or a volunteer service, which are available in some areas. Joe Balistrera, owner of Pest and Wildlife Control, gets between 10 to 30 calls for venomous snakes year, nearly always for timber rattlesnakes, in New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. He charges between $150 to $400 for a venomous snake removal, depending on the distance and difficulty of the job.

With a permit, you can legally collect one timber rattlesnake from the wild to keep in Pennsylvania, though the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission “does not recommend keeping venomous reptiles as pets.”

Pennsylvania also hosts a tightly restricted hunting season in the summer during which you can, with a permit, take or kill one copperhead or one male timber rattlesnake over a certain size.

What to do – and not do – if you get bitten

In the unlikely event you get bitten by a snake, get a picture of the snake if you can, but don’t interact with it.

If you can’t get a picture, try to remember the snake’s shape and color; the shape of their pupils and whether they had fangs are telltale signs as well.

A description will help determine whether the snake was venomous, and therefore whether you might need antivenom. If you see two puncture holes where you were bitten, that’s consistent with fangs of a venomous snake.

Walk don’t run to the car and drive or get a ride to the nearest hospital, said Stechert. Don’t panic, don’t speed.

That was Stechert’s mistake when as a teenager he was bitten by a rattlesnake he’d been pursuing in Cuddebackville, N.Y. He and his friend flagged down a police officer who escorted them to what was then St. Francis Hospital in Port Jervis, N.Y., at 90 miles an hour, creating a more dangerous scenario, in Stechert’s mind, than the one to which he was responding. “My friend was not a good driver. I was terrified,” said Stechert.

You probably won’t know right away whether a snakebite is serious: if the bite contained venom or how much. With most bites you’ll begin to feel pain within 30 minutes if venom has been injected, said Keyler.

Antivenom comes with its own risk of side effects and you don’t want to take it unnecessarily, stresses Stechert, though it’s gotten a lot safer in recent years. Only in about 30 percent of venomous snakebite cases does the Poison Center recommend treatment with antivenom, said Eggleston. “There’s always some risk of allergic reaction, so that’s why we don’t want to just give it if there’s no indication,” he said.

It’s a good idea to know whether your hospital carries antivenom (see sidebar). If you’re not sure, head to the nearest ER and call poison control en route, said Eggleston. They will track down the nearest antivenom and coordinate getting it to the hospital.

Most hospitals in regions with venomous snakes carry antivenom, but not all. “You can’t always assume that. Antivenom is not cheap, but independent of the economics, snakebite’s not a common occurrence,” said Keyler. “You tend to stock drugs you’re going to use frequently.”

Antivenom costs a couple thousand dollars per vial and a treatment might run from 10 to 15 vials, said Eggleston. The Upstate New York Poison Center recommends that hospitals in the region carry antivenom, but has no way to track whether they have it in stock at any given time, he said.

Who’s most vulnerable?

People at increased risk of severe snakebite reaction include those with autoimmune disease, cardiac disease, kidney disease, history of allergies or hypersensitivity to a lot of things, or a previous venomous snakebite, said Keyler. If you tend to be highly allergic, said Keyler, it’s a good idea to carry an epi pen, which is effective against allergy to snake venom.

Anyone in a remote situation, whether you’re back-country hiking or you live in a rural area far from a hospital, is also at heightened risk of faring badly. Carrying a cell phone or walkie-talkie when you’re out in the woods can be a critical timesaver, said Keyler, so you can call or radio for help to meet you.

Balistrera, of Pest and Wildlife Control, wears snake chaps and uses six-foot tongs and a bucket when responding to venomous snake calls, often in remote areas of Northeastern Pennsylvania. He’s never been bitten. “I don’t want to jinx myself,” he said. “I work smarter not harder. I don’t know where the closest, freshest antivenom is. You never know who has it in stock or how aged it is. My chances of survival are lower because of the areas I work in.”

A Connecticut man bitten by a rattlesnake in New York last year spent a week in a medically induced coma at Hartford Hospital, where he’d been airlifted because the hospital he drove himself to did not have enough antivenom, according to Eyewitness News.

A nine-year-old Arizona boy had a finger amputated last summer after he was bitten by a rattlesnake on a camping trip, 40 miles from the nearest hospital, the Arizona Republic reported.

‘I thought I grabbed a thorn or something’

When Charles Kieffer got bitten by a copperhead while doing yard work in Frankford Township, N.J., in 2001, he didn’t realize it right away.

Kieffer, president of Kieffer Electric, had reached underneath a tarp covering topsoil, which was held down by rocks, to straighten it after some bad weather. “I got pinched in my left thumb. I thought I grabbed a thorn or something.”

It wasn’t until he walked the tarp back that he saw the copperhead, which tried to bite him again in the ankle before he gave it a kick and it moved off.

He called the hospital, then Newton Memorial Hospital, and a volunteer – after putting him on hold twice – told him to check in with his family doctor. He got back on his tractor.

“Within half an hour my thumb felt like someone was twisting it off,” he recalled.

Two hours later, he was in the emergency room at Newton Memorial, where they kept him overnight and gave him morphine, but had no antivenom in stock. (Newton Memorial Hospital merged with Atlantic Health System to become Newton Medical Center in 2011, and now carries antivenom.)

By the next morning, Kieffer’s arm was three times its size. “I looked like Popeye,” he said.

A hand surgeon suggested cutting it open to relieve the swelling. Kieffer, who makes his living with his hands, said no way.

Two red lines were streaking up his forearm by the time he was medevaced to Jacobi’s Snakebite Center, where they tested his blood and gave him antivenom. A surgeon, who to Kieffer’s dismay looked like a teenager, ably snipped the top layer of now-black skin off his thumb and peeled it off “like a grape” to reveal a pink layer underneath.

The next morning he was fine.

During two days under observation at the Snakebite Center, Kieffer got a front-row seat to ill-fated snake-man interactions. One man, flown in from Connecticut, was dead on arrival, having been bitten by his pet asp. “This idiot” from Pennsylvania was brought in after drunkenly attempting to kiss his pet rattlesnake on the nose to impress his friends at a party. He’d been bitten twice in the face, which had blown up like a pumpkin. He needed skin grafts, a process that was going to take months.

After the copperhead bite, the tip of Kieffer’s thumb from the fold up lost feeling. As the nerves ever-so-slowly started to regenerate, occasionally he would drop something, his body wrongly telling him it was burning hot. It took 20 years until it was finally back to normal.

Keiffer doesn’t think of himself as part of a brotherhood, partly because he didn’t know anyone else in that club until his friend, Parker Space, got bitten last year.

His takeaway? “I don’t stick my hand under a tarp without pulling it back first.” He keeps his lawn and hayfields mown short. When there was a rattlesnake trying to get into his pole barn, he scared it off by tapping a shovel nearby, then called Space to come relocate it.